Op Je Oren Online

Audio bij de Slagwerkkrantrubriek

Slagwerkkrant Plus 19-06-2009 00:23

Extra spannend was hij dit keer, de Slagwerkkrantrubriek Op Je Oren. Drie vrijwilligers uit de redactie luisterden zonder enige informatie vooraf naar Mr. A.T. van drummer Arthur Taylor. Zouden ze zachtzinniger zijn geweest in hun oordeel als ze hadden geweten dat dit een van de favoriete platen is van auteur Hugo Pinksterboer? We zullen het nooit weten, en dat is nu juist het mooie van blind recenseren; puur afgaan op je oren dus...

Mark Eeftens

De drummer van dit jazzkwintet in de jaren-zestigtraditie speelt met een wat slapper gestemde, kleine bass, en zijn snare klinkt me opvallend laag in de oren, met de hihat meestal op twee en vier, en de nodige vrijheid in het ridepatroon. Is dit iets ouds dat opgepoetst is, of iets nieuwers van een drummer die zijn klassiekers kent? Vooralsnog geen idee! Het zal wel een blazersplaat zijn, want die krijgen wel eens meer ruimte dan soms boeiend is…

Dick de Waal

Het drumwerk vind ik ‘vlakjes’ en de saxpartijen klinken penetrant en blenden te weinig. Aanzienlijk mooier is de start van een integer aandoende ballad, maar die gaat helaas weer over in een vrij onsubtiel gedrumde swing. Track 6 is mijns inziens qua compositie en invulling het sterkst, afgezien van de slordige drumsolo. Als het niet vernieuwend bedoeld is, vind ik het best aardig.

Mark van Schaick

Deze mainstreambebop pakt mij pas in de uptempo stukken. Maar de ballads... Het klinkt alsof de drummer in kwestie hard met zijn brushes zit te meppen waar subtiel begeleiden op z’n plaats zou zijn. Een wat oudere drummer, lijkt me, die iets strammer uit de hoek komt dan in zijn jonge jaren.

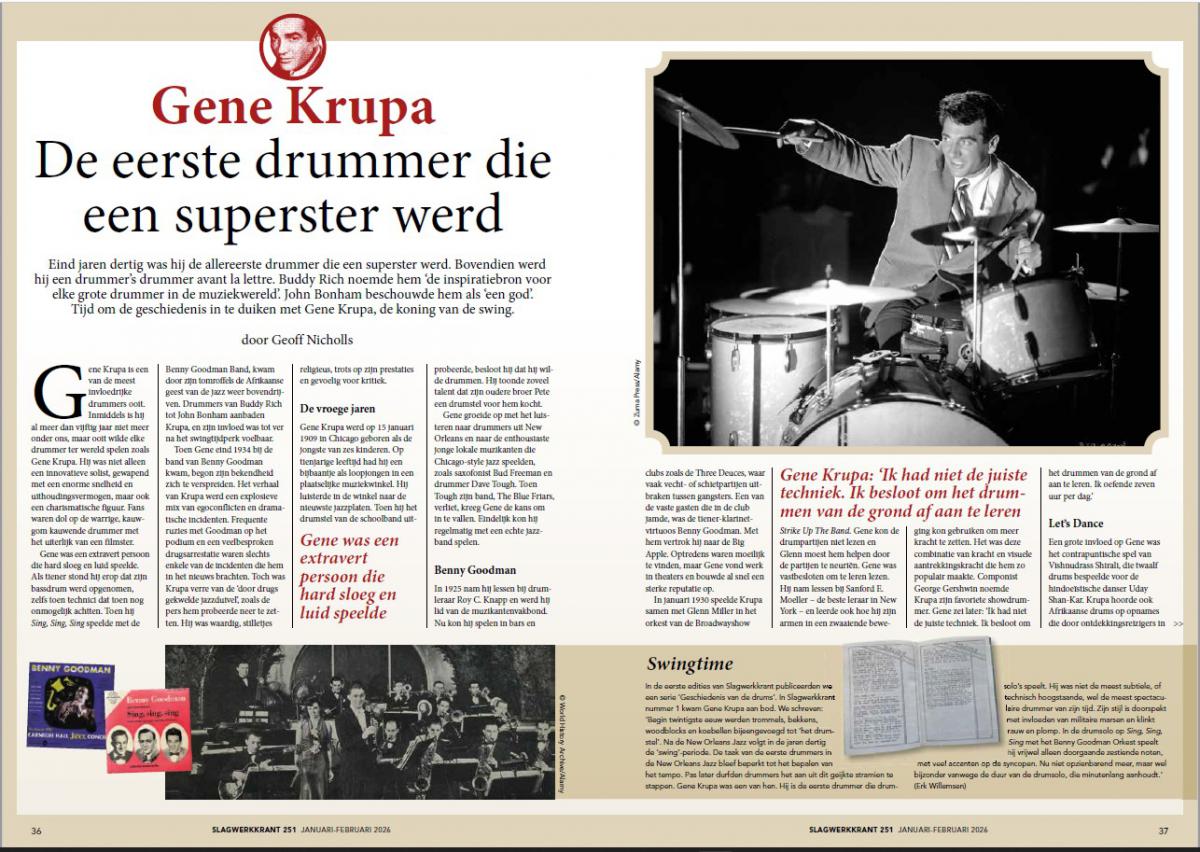

In Memoriam Arthur Taylor

April 6, 1929 - February 6, 1995

Arthur Taylor, A.T. or T. for friends, died on February 6, 1995, at the age of 65, in a New York hospital. He was one of the most sought after jazzdrummers in the fifties and early sixties, recording classic albums such as John Coltrane's Giant Steps and Miles Davis' Miles Ahead. Not a great technician, not an innovator, but one of the most down to earth, hard swinging and inspired drummers that ever lived, with a great sense of humor and spirit, in music and in life. Passionate, in every sense of the word. As a tribute, we present the interview that he did with Hugo Pinksterboer in october 1993. An abbreviated version of this article was published in Dutch drummer’s magazine Slagwerkkrant (# 60, march/april 1994).

"Yeah, I like to have fun. I'm looking to have a good time. And when I really look at me, basically, I beat the game of life. Because I don't have to wake up in the morning. I can sleep late. I can have a nice time in the music, and I can have somebody come up to me and say: "You're great." Or I can meet a beautiful woman who is impressed by something that I do, on the drums. That's an ideal situation. It's better than having to go to some job, early in the morning. So I beat the game. It's really an advantage for a black guy, in the way the world's set up: I can meet people I could never meet otherwise. And I can meet people for my book that I could never meet playing the drums...

Because of the book people sometimes refer to me as an author. I don't. I consider myself a chronicler. I keep records of the time. You know, the first thing in my new book really flips people out. I say to Dexter Gordon: "You have been a musician who's been around for many years. One of the founders of be-bop. So I'd like to know your impression of free music." And he replies: ‘My manager told me there would be days like this...’ People told me they just put the book down. This is enough, this cracks me up [laughs]. To this date that's the most famous statement in this book."

Your discography lists just some of the names of the numerous artists you performed with. Looking back, you’re not happy with everything you did back then, are you?

"I'm in a position now that I can do these things again, and I can do them better. You know, maybe some people develop quicker than others. I think I'm a little slower to develop, slower to grasp things than some people. There are drummers who go to a record date and cut it right down. It takes me a little longer. But once I learned, I never forget. I can play an arrangement of thirty years ago. I hear the first two bars and it all comes back.

One of the most famous record I ever made is, eh, the eh… Thelonious Monk Town Hall record, on Riverside. It's a big band. With a thirteen or fourteen piece band. And everywhere I go people say `you were fantastic on that record.' But I don't like to hear it, because I don't play well. You know that for yourself. The individual knows when something is good, no matter what anybody says. That's frustrating, in a way."

Broadening My Knowledge

"Also, I'm not a trained musician, although I did take some training, but that was after I had made a hundred and some records. My mother bought me a set of drums for Christmas 1947 and I was playing in January. And I haven't stopped yet. Simple as that. Teachers couldn't stand me, because I just wanted to play. I didn't want to go though the mechanics of it, the technical aspects. I didn't want to be bothered. I didn't miss that. Now Kenny Clarke was always after me to study, for my own benefit. To broaden my musical knowledge, to be able to work more, to be able to make more money. And I would be a better musician.

When he opened his school in Paris, with Dante Agostini, I started to study there.

I had to fight him physically in order not to go, so it was easier to go there. I'm serious, man. He was vehement about this, you know: ‘Come on man, you got to better. You got to do it. I'll show you how to do it. It will cost you nothing, just a little work.’ It's nice to have someone think enough of you... That's something to be proud of. I studied with him for two or three years.

People thought I was going crazy: I studied with kids, twelve year old boys, first time they picked up a drumstick. We did group sessions. I started right at the bottom. It was strange, man. After a very short period of time the professors, Klook and Dante Agostini, would use me to demonstrate, because I was professional anyway. I could phrase the partitions better then the kids, so they could learn that from me. I could interpret it. I could play it clean, and I could phrase it the way they wanted a drummer to phrase it. So that was interesting. Then it got to the point, after a year or so, that I could play all the stuff, and I could play as clean and as articulate as anybody in the school. So then they wanted me to teach. Then it became a pressure, cause I couldn't make any errors anymore.

But I started teaching, and I still do. And I learned to play 6 and 8 and 10 stroke rolls, instead of just 5, 7 or 9. I wasn't aware of that until I studied with Kenny. That opened another dimension for me."

What’s the main difference between the records you made before and after Kenny's school?

"I don't know. Eeehhhm… That goes into development also. I believe you should get better. As I was just telling this young sax player, Abraham Burton: ‘I thought I was playing better now than I ever played.’

With Kenny Clarke I started to find out what I was doing and then I could refine it. It broadened me. I found I could do things on a wider scale. I could develop things more. I could develop a solo. In Europe I was required to play solos. In the US I didn't have to do that. I just go out and swing. But when I came to Europe with my reputation, people wanted me to play a solo. In Europe, people kind of expected solos from me, because I had a reputation.

Thelonious Monk always had me play solos only on ballads. Ruby My Dear, Round about Midnight. It was weird, man, it was really weird [laughs]. Can't explain how I did it. It seems like everything is cut in half. In a ballad you can't play a solo like you normally would: you have to device something else. You're not supposed to go right back in double tempo. Monk wouldn't let me [laughs]. But it has helped me quite a bit, in the end. Slows you down. You become more articulate. You have to play more articulate if you play slow. It's easier to play fast than slow. If you play fast it is going by. If you make a mistake slow, it stands out, like a sore finger. And yes, I made my share of mistakes.

One of the ‘mistakes’ Taylor was known for, at a certain period of his life, was dropping sticks - and the way he then responded:

"I was playing with Johnny Griffin for some time and I was dropping like ten sticks a night. And I was becoming very frustrated, you know. I said, What the heck is happening. When I dropped a stick he would laugh, but I became enraged with myself: what the hell's happening, man. I even would use profane language. Yet I would get the biggest applause I ever had. And I said to myself, well, that's really to much. People applaud more when I drop a stick than when I play a good solo. And Griffin says: ‘Yeah, but the people see how frustrated you are when you drop a stick, this is subconscious, see, so they see how frustrated you are, and they know you're giving everything you got, and that's what they come there for. They love that! He's giving everything, is what the audience feels.’"

The total commitment that showed when Art Taylor and Johnny Griffin performed was also very noticeable in his own group, Taylor's Wailers.

"Nobody's gonna have a drink when someone else is having a solo. It has to do with interest in what you're doing. And in the people you're doing this with. And, also, you might hear something that you can play, later. The first thing I want to have on my bandstand is total commitment to concentration. What I tell them is that ‘I don't care about your mother or your father who died. I'm sorry about all that, but I haven't got time to think about that now. When we're playing music, that doesn't enter into it. When you finish this set, you may go back to reality. But when we're playing that doesn't exist.’

You know, I'm just skeptical about hiring a musician who's even married. I am even more skeptical if he has a baby. And even more if he uses drugs. Or if he is a womanizer. Because the concentration is not going to be on a level that I know is required to do what we can possible do. When he has a baby he has to think about that baby: that is top priority. And I want top priority for the music.

I have been around so long, and played with so many great musicians - I hope something has rubbed of on me- so I'm skeptical. I take a good look at a guy, and if he wears an earring, I'll ask him why? Does it make you play better?"

And what exactly is the difference between an earring and a moustache?

"A moustache comes naturally... "

A beard does too, and you take that off?

"Yeah, but you can take an earring off too…"

Drummers Are Superior, Period!

"I have never been interested in being a leader: I was having too much of a good time being a sideman. And I know the responsibility to be a leader, as I played with Miles, Coleman Hawkins, and Bud Powell. They were all great leaders. Being a leader is not about being a good player – that too, of course – but it's about a certain manner or decorum which is necessary to maintain self-respect and respect from the band members. A degree of discipline that I was not interested in having.

At this time I find it much better too hire young musicians and try to develop them into what I think is correct and into what they think is correct. When we both think it's correct I know I'm on the right track. Young people are always discovering, and I discover with them at the same time. It has to do with youth. And with young women. That keeps you young too. I believe that. I really do..."

What turned you into being a leader?

"I was a sideman, and I have a reputation. Made all those records, and may be I outlived my youthfulness. Maybe it was just difficult to get a job as a sideman. Most of the people I played with are gone, I'm sorry to say. Bud and Trane, Gene Ammons, Miles, Monk. Some are still her, like Jackie McLean. I did a tremendous volume of work with him too, and he's still around, thank goodness."

A lot of older jazz drummers started playing with young musicians: Art Blakey, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, yourself.

"You ask me why? We have to move on, too. You can't stop. And maybe you can develop something. And, again, most of the guys are gone."

Do drummers live longer, then?

"I tell you what kind of cynical person I am, and I wouldn't say it if I felt qualms about it, you know... When I returned to the United States in 1981, after having lived in Europe, I wanted to see what these people were really at. I said, I try this out, see how it works. I would make a brash statement, to someone who I knew couldn't take it. I said: ‘Drummers are superior to everybody: this transcends race, religion, national origin, how much money you got, how beautiful your woman is, what kind of car you have, what kind of house you have, how great your family is. This transcends all of that. Drummers are superior, PERIOD!’

Now you can't have a statement like that without backing it up, so I had my lines: First of all, I have been a drummer for forty years, so I can't be that weak: I have been carrying them things all over this planet... And then we give, because we play for the sax, we make the trumpet sound good and we play for the bass. And then we play a solo by ourselves. And I don't care, even the worst drummer in the world, when he's at the top of his stuff, he breaks the joint up. People go off. It's phenomenal to see. When he's at the top of his stuff, he breaks, he tears the place up. A drummer is the man. If you have a sad drummer, you have a sad band. If you got a good drummer, you got a good band. Simple as that, no matter what the guys are playing.

Plus the fact, you know this joke, that drummers are supposed to be crazy. So I was just baiting them. I like to do that... I can agree with you and still argue with you. Makes my point stronger. I want you to strengthen my point, so I want to argue with you. It helps me reaffirm my thoughts. And I tell you that I agree with you, but I will argue this point with you too. We can have bitter arguments on the subject, but it will make me stronger. It makes things clear, so you know where you stand."

Lyrics

"I was greatly influenced by Charlie Parker. And on one of the first occasions that I played with him he told me what I had to do to get better: I had to learn to sing all the lyrics of all the standard songs that we did. And then, when I was playing, subconsciously, I wouldn't play something which was uncouth, cause I knew the lyrics. The lyrics help me to manage. I never get lost. Well, I get lost once a year, but that's usually when someone throws me off...

People say I play very precise, very clear. And less can be more. Miles Davis proofs that. He would take a pause, that's like breath taking. I can swing, that's my specialty. Kenny Dorham used to say: ‘Boy, you're something else you know. When you get in that crouch, that's it. It's all over, you can forget about it, But why don't you just start out in that crouch, why do you have to arrive to it, each time...’" [laughs].

Mr. A.T.

"You know, that's why I like the tune Mr A.T. so much, the one that Walter Bolden wrote for me: all the beautiful women always sing that tune. And I play for the ladies. If the ladies don't like it, it doesn't excite me too much either; Cause if the ladies like it, the guys will like it anyway. Even if they don't like it...

Mr A.T. was recorded in two hours and fifteen minutes, and that includes a ten minute cigarette break. That's the way I record, yes sir. We all knew what he had to do and how we were going to do it. We recorded it the old method, directly to tape. And that's was what the cd is. We had to mix nothing, nothing like that.

You know, everybody goes in the booth at Rudy Van Gelder's studio. And I don't go in there, I am the only one. I'm not going in that room. And the record doesn't sound like other records. We played it just like you play music and we left. "

On one of the tunes you play brushes only. Most drummers would switch to sticks, after the first two choruses.

"How that came about, well, that's Philly Joe Jones. I'm lucky, cause people always try to show me nice things about music and drumming, and all that. I like that because then people really think something of me. And Philly Joe showed me these brush strokes. He had about fifteen of them, and I just used only about one or two. He said: ‘What's the matter with you, you gotta learn these strokes.’ ‘Man, I don't want to learn those strokes, I want to go out and have some fun with the guys. Or with the girls, or whatever.’ And then I did a concert, a tribute to Bud Powell, and one of the critics of the New York Times wrote that my brush technique was so impeccable. It was unbelievable. The touch of it. So you like some brushes, I'll play some brushes for you.... Subconsciously it kind of keyed me on playing brushes. Plus that piece kind of fits with the brushes. And I can play them as hard as sticks, even."

Total Attention

"The first thing I let everybody know is first of all when we are playing in a club, and the people are talking, then we're not playing. if you are really playing something nobody's gonna say a word. The waiter won't even serve a drink cause he stops in his tracks. And if people are talking, I'm gonna stop them. I'm gonna do something. By playing, or whatever. I'll go by any means necessary, crack a joke, anything. You have to have total attention. I don't go for applause, I go for attention. Because people can be talking all through your stuff and give you a big applause, but they didn't hear a thing you played. It's like automatic, I don't like that. They put a sign up: it's time to applause. And we haven't played a thing if we come of stage and we're not laughing.. Get out of here, that's no music. Music is supposed to make people feel good, and if the people who are playing don't feel good, how are people who have been working all day, who want to wash away that, supposed to feel good? So we have jokes, we do all kinds of things to entertain the people. Not to be prostituting yourself, but to let the audience have a good time."

But Is It Art?

You don't consider jazz an art form, is what you say in the liner notes of Mr. A.T.

"Yeah, yeah. I don't see how it could be an art form. Maybe it is, but to me it's not. I don't consider myself an artist. I don't have to go to work nine to five, I travel around and meet friends and make friends…"

"And I'm not an artist because there's so many criminal elements in it, there's heavy exploitation. I have been working for gangsters all my life. I worked for the Birdland Corporation, and they're gangsters. Mob stuff. I worked for those people for years. Pimps and whores, and drinks, and drugs. And well, maybe, that's art. If that's art, that's alright with me. But I don't consider it art; it's just about havin' some fun, you know?"

Are there any jazzmusicians you do consider artists?

"O yeah. Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins..."

Then what's the difference?

"Cause I don't work hard like those people. Cause those people strived and worked hard and studied. I don't do all that stuff man, I like to have a good time. I go on my natural talent.

I'm into having a good band, and that's all there is to me. You see people in jazz clubs in trance, like they're waiting for a message from god... that nobody's even giving. From a god that nobody knows, cause everybody had a different god anyway. People sometimes expect these messages from the musicians, and some musicians think they have to do that, and I hope they keep on doing what they're doing, cause I won't be doing it....

I would like to reach a point, not that I would ever reach it, of the humility and respect that Charlie Parker had. Because he never put anybody down. He always found something good. You have a good sound, or you handle your instrument well, or... And it is very easy to find bad points on anything I would like to...

I used to put people down. But I started again. People used to be scared of me. I was a pretty arrogant guy, I guess, I was playing with Bud Powell, you know, and that's a pretty lofty place to be. Don't speak to me, I haven't got time for y you. In the fifties, I was playing a show in the Apollo Theatre, with Art Blakey. A real all star band. Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley, Cecil Payne, and all the greatest guys... I was enthralled with all this, I was playing with the seventeen Messengers. And this man, who I found out later was Leon Thomas, comes up to me and he says: ‘A.T., I am on the show tonight, and may be would you have a little chat with me about how we are going to do it?’ Years later I am doing an interview with him for my book. And the tape is running and I say: ‘When did we meet for the first time. Wasn't that at Birdland?’ And he says: ‘No, that wasn't in Birdland. It was in that show with Art Blakey, and I came and tried to get you to talk with me to help me with my music, and you treated me like a dog.’ God... I was so embarrassed. I felt so terrible. I don't remember it either, but I knew I could do something like that back then. This was not evil, this was just dumb. How can you get so dumb...

Other than that, I can't complain about a thing. You see guys who never smile, don't have a good time, no fun or nothing. They're just geniuses. I just want to stay dumb as I am, not know too much, and have a good time, and a good rehearsed band. And a light, please..."

Jamaica

"I'm not on the road that much, no. I play mostly around the city, with my own band. I'm gonna be on the road, though. I want to go on the road, and I want to retire as well. I wanted to do that when I was 40, but I wasn't able too. I don't want to play like forever. I don't want to get to the point where I can't do what I can do. Up to the level... when I used to play with Griffin and Orsted and Kenny Drew, way back, in the 70's. The tempo's we were playing, pheeew. I wondered how long I would be able to keep this up, at the rate I was doing this.

So I thought about retirement. I don't know any musician who did retire, so far. I want to be the first... They all play till they die on the bandstand. I want to be first and make everybody mad. How the hell does he retire, you know. He don't have no money, he don't ever work, he's poor, you know....

My people are from Jamaica, and I spend a lot of time there. I like to walk at the see. I like the clean water and the fresh air, and the beautiful girls in bikinis. So I go and spent time there, have a rum punch, sit at the beach, watch the tourists, see the ladies running in bikinis. And the Jamaican people are famous for their good manners, whether they mean it or not. They make people feel good. It's like the Japanese. It makes you feel very nice. Americans can do that too, but you might drop dead that very second. Please drop dead, get away from me....

The Jamaicans are such gentlemen and so friendly. I insist on that, on good manners. Even more than the music. How you're gonna play good music if you're not decent? First of all you have to be decent. All the guys who I know who could really play were really decent people..."

Yet Charles Mingus, for instance, doesn't seem very decent to me, in his book, and the Buddy Rich's bus tapes do not make Rich come across as a decent man, either.

"Well, Mingus is not one of my favorite bass players... But I was always very impressed with Buddy Rich. I was lucky. My father always took me to the Apollo Theatre, when I was very young. before I started playing drums. Duke Ellington, Count Basie I heard J.C. Heard, who was really my idol on the drums. And he took me to see Buddy Rich, and he and Charlie Barnette. Those were the only white bands that could cut it in the Apollo. He took me to see Buddy Rich, and he had a broken arm. One arm in a cast. I saw this, and that man played the whole show, for the comedians and the dancers and what have you. He even played a solo with one hand. I have never seen anything like it in my life. Unbelievable. I can still close my eyes and see him do it. I told this to a guy and he said ‘Wow, I never would expect you saying anything nice about a white person.’ Oh man, what a headache; my manager told me there would be days like this..."

People always wanted you to practice, to study, and you're talking about retirement. Do you consider yourself a very relaxed person, or putting it in a more negative way, someone who likes to be lazy...

"Oh, yes, I am lazy. Very lazy. I admit it and I not gonna do anything about it, either... [laughs]. Except when I play. I love playing the drums more than anything. I rather play the drums with a good band than having sex – and I love sex as much as any human being. But nothing like playing the drums, playing good music. That's sexual right there, anyway. If you talk to a woman that's sexual, you know. Could be someone's grandmother, that's still sexual. There's always that little fraction of flirtation, a joke, or something friendly, something nice and kind. Nothing evil. It's linked in there, in improvised music. That's what attracts women."

At the same time you refer to yourself as the King of Rehearsal.

"I'm the king at the same time. I'm next to Lionel Hampton, the guy makes a joke about this, but when the band gets there we're making two hour records, and when the people hear us they know everything is in order. For Mr. A.T. we have done some twenty three hour rehearsals. You can just sit down and play with people that you know. We didn't rehearse all those records I made in the fifties and sixties. Cause everybody is looking for the same thing, driving for the same point. But when you're playing with people that you're not familiar with, young people at the same time, and you want to try to make something cohesive, the best thing is to rehearse. So we make moves that look like we don't know what we're doing. But we do know what we're doing, all the time. Really, when we go and play I'm sorry for any band that has to follow us. Cause we are really out there."

-- Hugo Pinksterboer

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Arthur Taylor played on numerous records. All albums below have been released on cd as well.

- Gene Ammons - The Big Sound (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- Gene Ammons - Blue Gene (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- Art Blakey - Orgy in Rhythm, Vol. 1 & 2 (1957, Blue Note)

- Kenny Burrel - All Night Long (1956, Original Jazz Classics)

- Kenny Burrel - All Day Long (1957, Original Jazz Classics)

- Donald Byrd - Byrd in Hand (1958, Blue Note)

- John Coltrane - Dakar (1957, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - Traneing In (1957, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - Tenor Conclave (1956, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - Wheelin' and Dealin' (1957, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - Soultrane (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - Settin' The Pace (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - Black Pearl (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - The Standard Coltrane (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - The Stardust Session (1958, Original Jazz Classics)

- John Coltrane - John Coltrane and the Jazz Giants (1958, Prestige)

- John Coltrane - Giant Steps (1959, Atlantic)

- Miles Davis - Collector's Items (1953-1956, Original Jazz Classics)

- Miles Davis - Quintet/Sextet (1955, Original Jazz Classics)

- Miles Davis - Miles Ahead (1957, CBS)

- Miles Davis - Live in New York (1957-1959, Bandstand

- Kenny Dorham - Quiet Kenny (1959, Original Jazz Classics)

- Kenny Dorham - Matador/Inta Somethin' (1962, Blue Note)

- Tommy Flanagan - Thelonica (1982, Enja)

- Red Garland - 13 cd's (1957-1959, allen op Original Jazz Classics)

- Dexter Gordon - One Flight Up (1964, Blue Note)

- Milt Jackson - Soul Brothers/Soul Meeting (1957-1958, Atantic)

- Rahsaan Roland Kirk- Kirk's Work (1961, Original Jazz Classics)

- Jackie McLean - 6 cd's (1956-1957, allen op Original Jazz Classics)

- Jackie McLean - Jackie's Bag (1959-1960, Blue Note)

- Jackie McLean - Tippin' The Scales (1962, Blue Note)

- Thelonious Monk / Sonny Rollins (1953-1954, Original Jazz Classics)

- Thelonious Monk - At Town Hall (1959 - Original Jazz Classics)

- Thelonious Monk - 5 by Monk 5 (1959 - Original Jazz Classics)

- Lee Morgan - Candy (1958, Blue Note)

- Charlie Parker - The Bird You Never Heard (1950, Stash)

- Bud Powell - The Amazing Bud Powell, Volume 2 (1951-1953, Blue Note)

- Bud Powell - Summer Sessions (1953, Magic Music)

- Sonny Rollins - Moving Out (1954, Original Jazz Classics)

- Horace Silver - Silver's Blue (1956, Portrait)

- Sonny Stitt - Sonny Stitt Meets Brother Jack (1962, Original Jazz Classics)

- Lennie Tristano - Requiem (1955, Atlantic)

- Stanley Turrentine - Z.T.'s Blues (1961, Blue Note)

- Lou Donaldson - Quartet/Quintet/Sextet (1952-1954, Blue Note)

- Thad Jones - After Hours (Original Jazz Classics)

- Toots Thielemans - Man Bites Harmonica (197?, Original Jazz Classics)

Solo albums

- Taylor's Wailers (1957, Original Jazz Classics), with John Coltrane, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Ray Bryant, Red Garland, Wendell Marshall and Paul Chambers.

- Mr. A.T. (1991, Enja)with Willie Williams (ts), Abraham Burton (as), Marc Cary (p) and Tyler Mitchell (b)

- Wailin' at the Vanguard (1992, Verve) with Willie Williams (ts), Abraham Burton (as), Jacky Terrasson (p) en Tyler Mitchell (b)

Books